We are profoundly distressed to learn from sources in Arusha that a FOURTH elephant trophy hunt is believed to have started this Easter weekend in Enduimet, Tanzania.

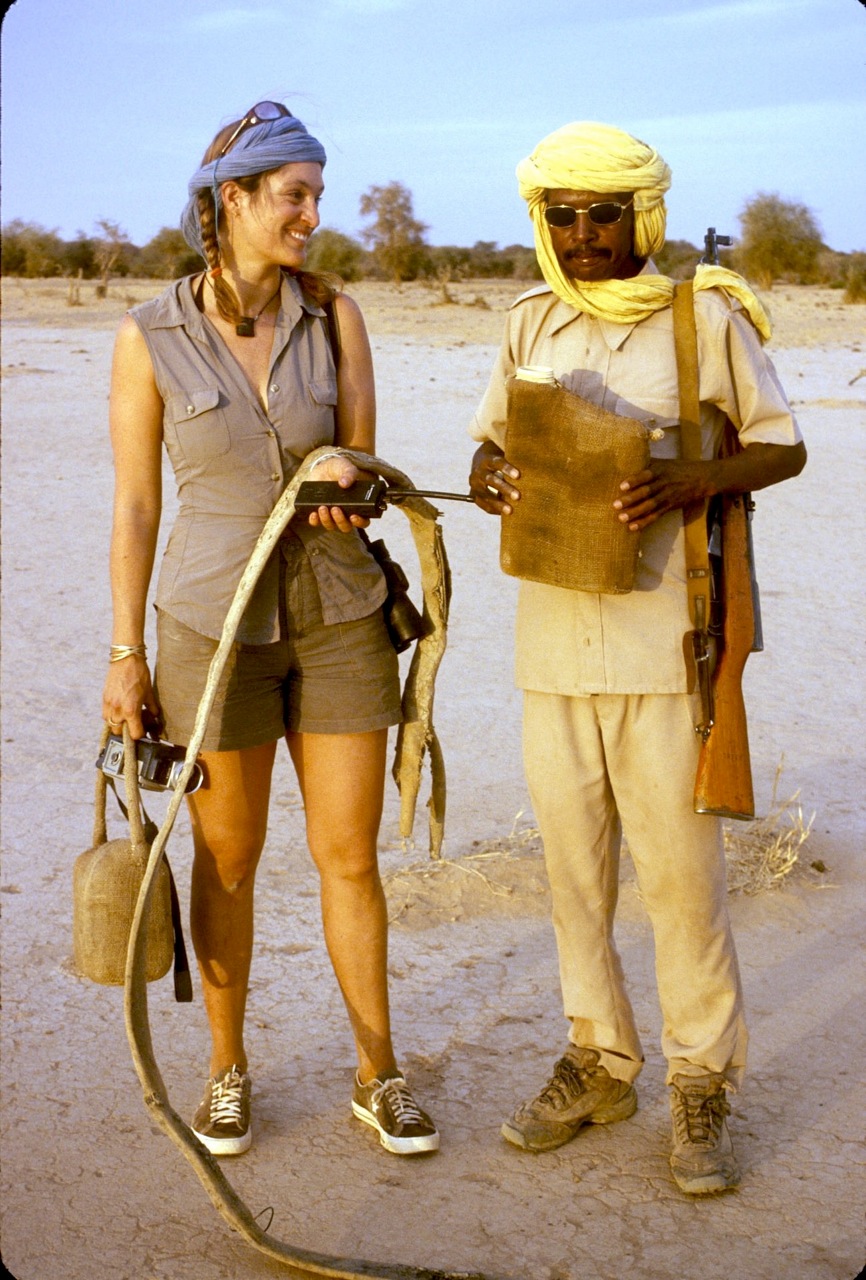

As longterm elephant conservationists, we are vehemently opposed to the sport hunting of these iconic and extremely rare large-tusked cross-border elephants – stars of Kenya’s tourism industry, numerous landmark wildlife series and photographic awards, as well as being of great cultural significance to the Maasai people with whom they share the glorious landscape at the foot of Kilimanjaro.

This avaricious killing by rapacious, profoundly UNETHICAL so called “professional” hunters from Kilombero North Safaris and their gullible, misinformed clients, is totally unacceptable and must be STOPPED!

If you haven’t already, please sign and share our petition to help put an end to the trophy hunting of Amboseli’s elephants in the Enduimet area of Tanzania: https://bit.ly/THPetition

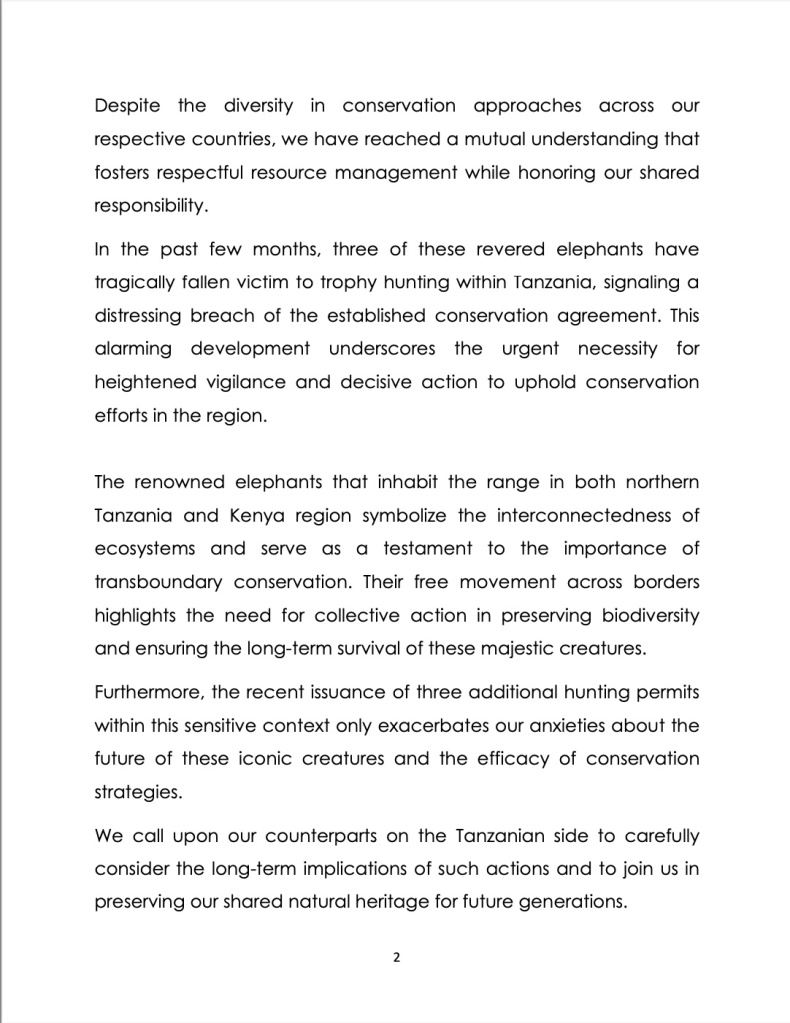

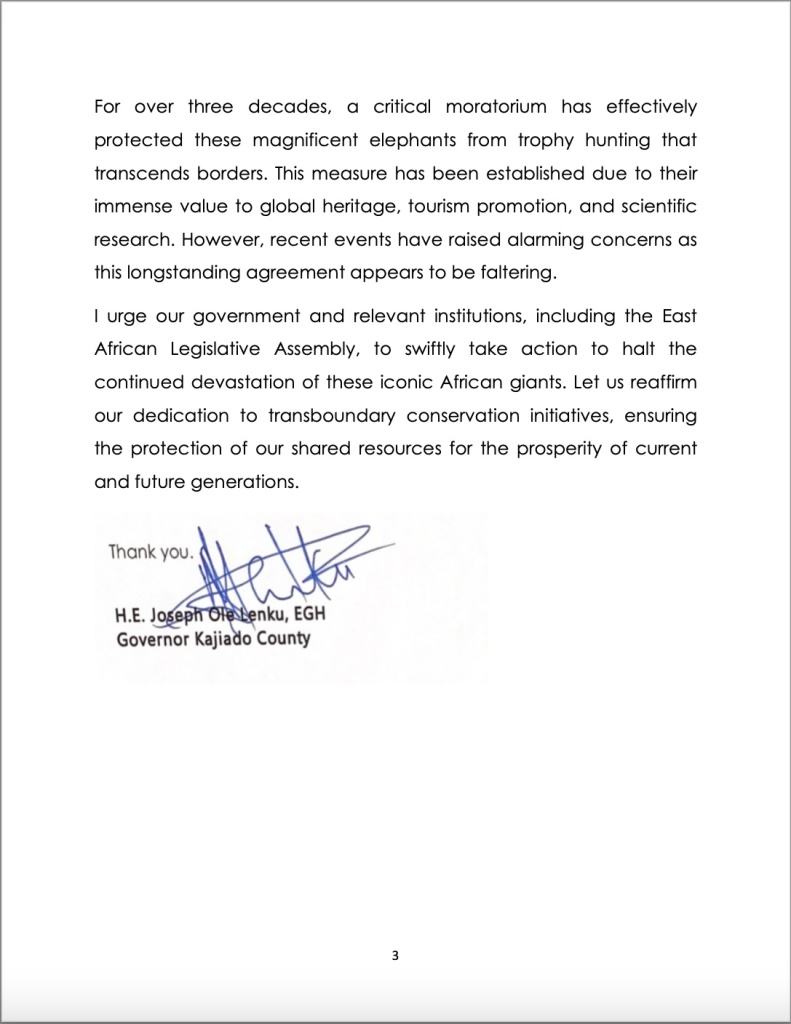

Yesterday, the Governor of Kajiado County, in which Amboseli National Park lies, called for an instant cessation of these hunts and made an urgent plea to the Govt of Tanzania to reinstate the moratorium that protects this unusual population of greatly beloved elephants.

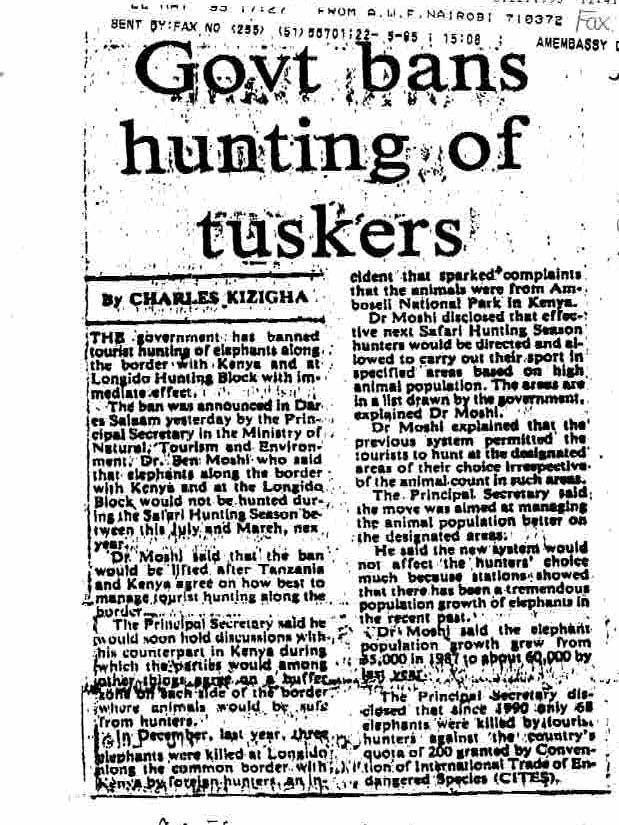

It beggars belief that trophy hunters are targeting these large-tusked males AGAIN, 30 years after a similar brutal spate of killing in 1994 caused a global outcry that led to the agreement to ban hunting of elephants in the West Kili/Natron area. Not only are each of these elephants known individually by name (many from birth) as the subjects of a 50 year research project by the Amboseli Trust for Elephants, the longest of its kind in the world, but they are so habituated to people and vehicles that shooting them is like sport-hunting one’s own pet poodle.

These disreputable killers at KNS are giving hunters a very bad name. THIS IS NOT CONSERVATION. This is environmental vandalism, that has as much place in the 21st Century as slavery and child brides. The very presence of these elephants is thanks to 30 years of successful cross-border conservation and collaboration between Kenya and Tanzania, that has now been ransacked by a few contemptible marauding individuals.

These tuskers are some of the last of their kind, and killing them for sport is unconscionable.

We call on the African Professional Hunters Association, TAHOA.ORG, and the ethical hunters of Tanzania to stand up and be counted! Your silence speaks volumes. Show us that you care more for conservation than you do for selling your souls for cash.

In light of these recent tragic events, our allies @ElephantVoices have asked us to share their highlights on the behaviour of males, their importance in elephant society and the unique challenges they face.

Young male elephants grow up in the tightly bonded society of females, and as calves and juveniles they maintain close relationships with their relatives and participate in the many social events that affect their family, albeit at a lower intensity than their female age-mates.

Male calves grow faster than female calves and their need for their mother’s milk is higher. They are more demanding, complaining more often and more loudly than their female counterparts. And during droughts, when their mothers don’t have enough milk, they die at a higher rate.

Around eight to nine years old, they begin displaying signs of independence, occasionally separating from their family unit for short periods. This gradual shift towards autonomy continues as they spend more time away from their familial group, gradually becoming more self-reliant.

During adolescence, young males tend to linger on the outskirts of their natal group, often seeking out interactions with peers from other families for playful engagements. Through these encounters, they learn about their own strength and size relative to their age-mates. They also exhibit curiosity towards the activities of older males, observing and sometimes imitating their behaviours. This early exposure aids in their socialisation.

As a young male’s interest in interacting with non-family males grows, it often serves as a catalyst for his departure from the natal family. Males are said to become independent when they spend less than 20 percent of their time with their natal group. The age of independence varies within the Amboseli elephant population, ranging from as early as nine to as late as 18 years old, with an average age of 14 years of age.

A claim often used by hunters is that they only shoot males who are old and no longer reproductive. Hunters refer to these males as “dead wood” “reproductively senile” or “senescent.” But the data from years of research by ElephantVoices and Amboseli Trust for Elephants (ATE), show that males between 35 and 55 years of age are in fact the primary breeders in a population, and that even males in their 60s still come into musth and mate successfully.

Some Amboseli males in their early 30s have tusks that almost touch the ground. They are only just entering their reproductive prime, but the size of their tusks make them targets for trophy hunters who mistakenly age them as “old.” This was depressingly evident with the first bull shot by Kilombero North Safaris, identified from a photograph by ATE as 35 year old Gilgil, a well known bull from the Amboseli population, that was only just entering his first reproductive years.

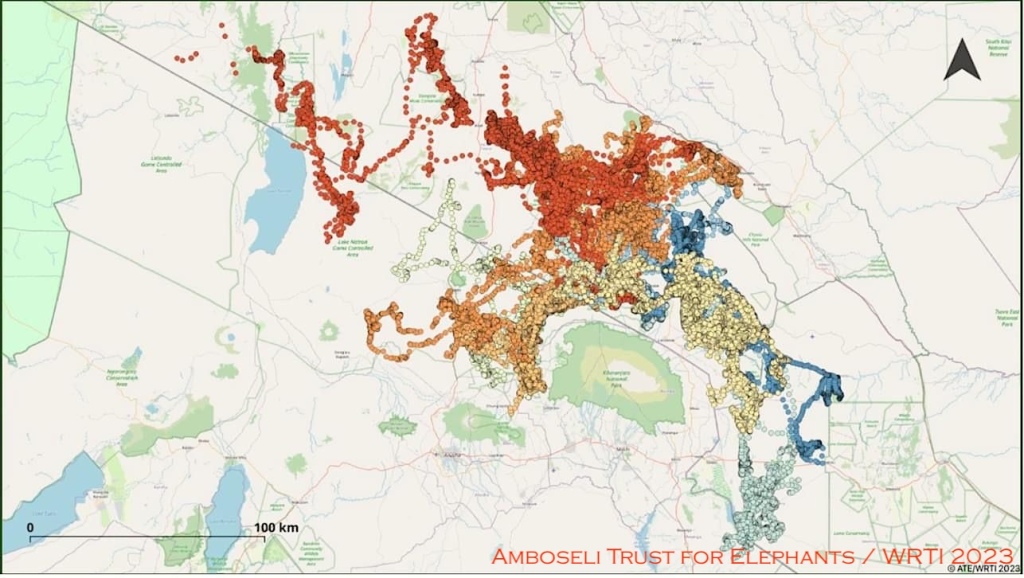

Key evidence showing how rapidly tusks can grow in mature males via our allies at Amboseli Trust for Elephants ![]() can be seen in these two photos of the famous Amboseli elephant known to many as Craig.

can be seen in these two photos of the famous Amboseli elephant known to many as Craig.

The first photo dates back to 2011, while the second was captured in 2018. The significant growth over this seven-year period is evident, with his head getting much larger, as well as the thickening and lengthening of his tusks. Typically, elephant researchers refrain from relying solely on tusks for identification due to changes over time. Instead, we primarily use characteristics such as ear patterns, skin markings, and other distinctive features on their bodies. These are the markers that were used utilized to identify Gilgil by ATE.

Craig, who is now 50, has another 10 years of being reproductively active, passing on his genes for large tusks to future generations. But, as long as trophy hunting continues across the border in Tanzania, older males like this are at very high risk.

Hunters’ continued assertions that they only target males beyond their reproductive prime is factually incorrect. Such misleading claims damage the hunting industry’s already fragile reputation. As does taking the lives of such magnificent individuals. Given that the shape and size of an elephants tusks are a heritable trait, the systematic elimination of males with large tusks will ultimately reduce average tusk length in a population.

We are proud to be part of an alliance of conservationist fighting for the lives of these bull elephants, and we thank ElephantVoices, Amboseli Trust for Elephants, Big Life Foundation, Wildlife Direct and Save The Elephants for bringing this desperate situation to the attention of the world.

If you haven’t already, please sign the petition to help put an end to the trophy hunting of Amboseli’s elephants in the Enduimet area of Tanzania: https://bit.ly/THPetition

© Max Hug-Williams – Habiba (collared) and the orphan herd

© Max Hug-Williams – Habiba (collared) and the orphan herd © Saba/STE – Rommel in 2008

© Saba/STE – Rommel in 2008